Gender and formality as determiners of labour migration from Ethiopia

A survey of Ethiopian women and men suggests that while many would choose to migrate to the Middle East, it is mostly women that actually do so. Women’s intention to migrate is much higher if they can do so through formal channels rather than informal ones.

International migration is often seen as a means to achieve significant income gains and spur economic development, primarily through remittances sent to migrants' countries of origin. However, there is growing concern over the financial, physical, and psychological costs associated with migration, especially in the context of informal or irregular migration. Issues – such as high costs imposed by human traffickers, dangerous conditions along migration routes, mistreatment by employers, and the risk of deportation – are particularly pronounced in the Middle East.

Ethiopians migrating to the Gulf

In the last five years, over 800,000 Ethiopians have moved to other countries to pursue work opportunities, and these migrants sent an estimated US$ 510 million in remittances back to Ethiopia in 2022. Both push and pull factors induce movement out of the country, including high unemployment rates, familial obligations, drought and other natural disasters, as well as overseas social networks, large demand for low-skilled work, and high wage differentials in major destination countries.

In addition to movement within the broader Horn of Africa, Ethiopian migrants tend to move along three key routes: the Eastern route (through Yemen to the Middle East), the Northern route (through Sudan and typically on to Europe), and the Southern route (through Kenya or Tanzania to South Africa).

Migration decisions and destinations tend to differ by gender

While there are slightly more Ethiopian men than women living and working abroad (54% versus 46%, respectively), destination decisions are highly gendered. For example, a recent national survey indicated that male migrants are more likely to stay in Africa, while female migrants are much more likely to migrate to the Middle East. The channel of migration is highly gendered as well. More specifically, many international labour opportunities through formal migration channels are only open to women seeking temporary domestic work contracts, particularly in Middle Eastern countries.

There are far fewer opportunities for men through formal migration channels, implying male migrants often resort to informal channels. However, the formal migration process can be lengthy, and often demand for international labour contracts outweighs supply, so some Ethiopian women also pursue migration through informal channels. Overall, a study in 2014 showed only 40% of Ethiopian migrants to the Middle East have proper legal documentation, suggesting informal migration is a common choice to reach this destination region.

Simultaneously, Ethiopia is experiencing a substantial number of returnees, especially from the Middle East, often deported after using informal routes and without proper documentation. To address these issues, the Government of Ethiopia is now working to expand and facilitate safe formal migration opportunities in Saudi Arabia and other countries, particularly for women. Against this backdrop, it is imperative to understand beliefs about the returns to migration through formal versus informal channels.

Studying motivations to migrate to the Middle East

In an IGC study, we investigate the relationship between migration channels and migration intentions. We are particularly interested in characterising who is more likely to opt for informal versus formal migration channels, and how gender, family dynamics, and beliefs about migration returns drive these decisions.

We gather a representative sample of 1,794 potential job seekers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia with a hypothetical job offer in the Middle East, eliciting their expected personal and household benefits and migration intentions. We emphasise that respondents who choose not to “take” the hypothetical job offer and move to the Middle East are choosing to remain in Ethiopia.

Our study also employs a survey experiment to explore how these intentions are influenced by migrating through formally or informally established channels. More specifically, we randomly assign about half of the individuals in our sample to receive the hypothetical job offer through formal means, and the other half through informal means. Finally, we collect basic demographic information on the respondent and their family.

Female migrants and female non-migrants differ in multiple ways

Overall, we find that approximately 60% of all respondents in our sample prefer to take up the hypothetical job offer—regardless of the randomised channel (formal or informal) type—and move to the Middle East, while the remaining 40% prefer to remain in Ethiopia. This result is similar when disaggregated by gender. However, when we restrict our sample to those who have previously migrated to the Middle East (12% of our sample), we find almost 90% of this group is women—emphasising that most of the job opportunities in the Middle East are for positions typically held by women, specifically in domestic labour.

Next, we compare differences between Ethiopian women who have previously migrated to the Middle East and those who have not.

- We find that female migrants, on average, are about four years older and have about one year less of education than female non-migrants. This aligns with data showing female migrants to the Middle East tend to be uneducated and perform low-skilled work abroad.

- We find female migrants are more likely to be married, have more children, and come from slightly larger families than female non-migrants, suggesting temporary labour migration may be an attractive mechanism for Ethiopian women to provide for their families.

- Female migrants are also more likely to be the household head and less like to be the daughter of the household head than female non-migrants, indicating their central role in household decision-making processes, including migration decisions.

- Notably, women who have previously migrated to the Middle East have, on average, seven more social contacts in the Middle East than women who have not migrated. Social networks evidently play a crucial role in facilitating migration, providing support and information to migrants, particularly women who may rely more on these networks due to cultural and social norms.

- We find that female migrants are more likely to be unemployed, expect to earn less, and be less happy if they were to stay in Ethiopia compared to taking up the hypothetical job offer and moving to the Middle East, highlighting persistent economic and wellbeing factors that may motivate migration decisions for Ethiopian women.

Women strongly prefer formal migration channels to informal ones

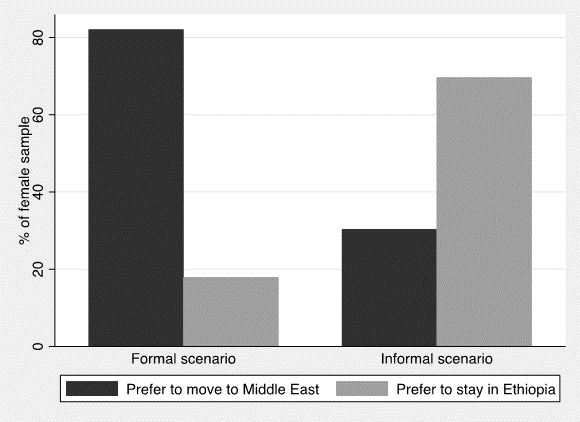

More broadly, when comparing migration intentions among all women in the formal and informal migration scenario —regardless of previous migration history—women in the formal scenario group are much more likely to prefer migrating to the Middle East for work over remaining in Ethiopia (see Figure 1). This finding is flipped in the informal scenario group, however, where women are more likely to prefer remaining in Ethiopia over migrating informally to the Middle East for work.

Figure 1: Women’s preferences among formal and informal migration

Notes: Women are more likely to migrate to the Middle East when offered a formal route and more likely to not migrate and remain in Ethiopia when offered an informal route for migration.

Several reasons are possible for this disparity. The informal migration scenario was associated with lower expected earnings and reduced expected wellbeing and work satisfaction for our survey respondents and their households. Informal migration is also riskier, so when presented with this option, women may be more risk averse and prefer to stay in Ethiopia. This highlights the importance of formal migration opportunities, which not only provide better expected outcomes for migrants, but also reduce the risks associated with informal migration, especially for women.

In conclusion, as migration is a significant livelihood strategy for many, there are implications for gender dynamics and migrant and household wellbeing. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for designing effective policies and interventions that promote women’s empowerment in migration decision-making.